“We are ready to meet the needs of a new generation of customers in a new era of communications and entertainment.”

– Edward E. Whitacre, Jr. Chairman and CEO, AT&T

When the "Unthinkable" Happened

View from the AT&T Merger Frontlines

In early 2005, a corporate maneuver once deemed "unthinkable" became a defining moment in American telecommunications history. SBC Communications, a regional offspring of the Bell System's 1984 divestiture, announced its intent to acquire AT&T—its former parent and a once-dominant force in global communications. The $16 billion deal, initially met with skepticism and political scrutiny, would become one of the most consequential mergers in the modern telecom era. I was 28 years old and, somewhat improbably, managing the California War Room in San Francisco—a nerve center for the public affairs campaign underpinning this unprecedented transaction. The "west" region was a significant market for the company. Success hinged on seven Public Utility hearings going smoothly, among other politics and regulatory hurdles.

AT&T, the name that had once defined American telephony, was by then a diminished enterprise. The consumer long-distance business had eroded under regulatory change and technological evolution. SBC, by contrast, had quietly built scale across local and regional markets, positioning itself as a formidable contender in wireless and broadband. Still, the optics of a regional upstart acquiring a former global hegemon demanded not only operational integration, but narrative control. The War Rooms—in San Antonio and in key states like California—were created to accomplish just that.

Reconstituting a Legacy

What was at stake in this merger extended beyond synergies and balance sheet consolidation. This was about resurrecting a legacy brand, while aligning it with the future of digital infrastructure. SBC was no longer content with being a regional carrier. Its leadership, particularly Chairman Edward Whitacre, understood that the industry was moving toward a model of convergence—where voice, video, data, and mobile services would all be offered by the same entity. For that, SBC needed AT&T’s reach, patents, and institutional expertise.

But ambition alone doesn’t drive policy approval. The merger had to survive regulatory scrutiny at both the federal and state levels, and it had to do so against the backdrop of fierce opposition from competitors, consumer watchdogs, and ideologically motivated commentators. The Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice would eventually approve the deal, but much of the practical work happened in the states—especially California.

California: Campaign as Strategy

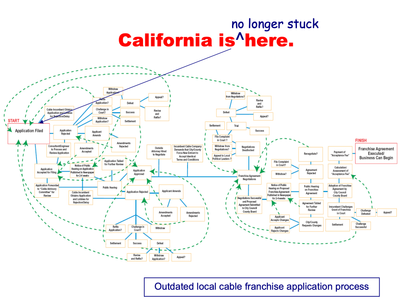

In California, the Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) held disproportionate influence over public perception and regulatory tone. The CPUC scheduled 14 public hearings in cities across the state. These sessions became flashpoints for public sentiment—and, more importantly, public theater. The hearings attracted not just concerned citizens but also orchestrated opposition from consumer advocacy groups, such as TURN and the Greenlining Institute, often joined by actors representing competitive carriers.

Our mandate in the San Francisco War Room was to shape the battlefield before the battle began. We worked in sync with Public Strategies, SBC's corporate affairs team, and local allies to ensure turnout, message alignment, and rapid response. We were not engaging in subterfuge; we were engaging in advocacy. Every public speaker, op-ed author, or civic leader who stood in support of the merger was part of a broader architecture designed to demonstrate societal benefit.

Polling data revealed a nuanced landscape. Most residential consumers were indifferent to the merger, but enterprise buyers cared deeply about infrastructure stability and service continuity. Using those insights, we emphasized the complementary strengths of SBC and AT&T: the former's regional and consumer focus; the latter's global enterprise capacity. Together, they would form a vertically integrated, technologically forward, and financially resilient entity—capable of competing not just with legacy rivals, but with emerging threats from VoIP startups, cable operators, and nascent wireless broadband providers.

The Mechanics of Control

The War Room itself was a hybrid between a newsroom and a command center. Our days began with 8 a.m. strategy calls, often involving teams in San Antonio, D.C., and across multiple time zones. We monitored national media, tracked regulatory filings, and maintained real-time dossiers on opposition activity. In the evenings, we would often brief allies or prepare for the next day’s hearing or editorial board engagement. Our virtual war room—a secure online platform updated in real time—allowed a geographically dispersed team to maintain message discipline and operational synchronicity.

At the core of our messaging were three pillars: complementarity, technological leadership, and industry stability. We drafted and disseminated thousands of talking points, white papers, PowerPoint decks, and Q&A documents. Much of this material was targeted not at the public, but at intermediaries: third-party validators such as labor unions, minority advocacy groups, think tanks, and small business associations. The Communications Workers of America (CWA), the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), and Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow/PUSH Coalition all publicly supported the deal, offering statements and testimony that reinforced our narrative.

Opposition as a Known Quantity

The loudest dissent came from ACTel, a coalition of competitive carriers that hired Gary Reback—the same attorney who had led the antitrust campaign against Microsoft in the 1990s. ACTel filed white papers, held press conferences, and purchased ad space in Roll Call and The Washington Post. But their arguments—mostly focused on job losses and market concentration—were not materially new. In many cases, we were able to preemptively rebut their claims by using their own past statements or economic inconsistencies.

Qwest, meanwhile, played a more cynical game. CEO Richard Notebaert alternated between opposing the SBC-AT&T merger and courting MCI, AT&T's closest peer. In public hearings and filings, Qwest argued for divestitures—but privately, they positioned themselves to acquire any spun-off assets. Our opposition research documented these contradictions and deployed them tactically during public comment windows and editorial board briefings.

The Human Element

What is often overlooked in post-merger analyses is the human cost—not in terms of job losses, but in cognitive and emotional bandwidth. Our War Room operated 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week. Team members slept with their phones on their nightstands. I occasionally slept in the war room. Every misstep had the potential to become a headline or a regulatory sticking point. The pressure was real. So was the camaraderie. We learned to trust one another’s instincts, to edit each other’s documents in silence, and to maintain decorum even under stress.

For me personally, the experience was transformative. I entered the year with a few wins under my belt from Missouri, and a sense of ambition. I exited with a toolkit of skills that I still draw upon two decades later: stakeholder mapping, regulatory fluency, media orchestration, and the ability to keep calm in rooms thick with consequence, big egos and loud voices.

Legacy and Perspective

The merger closed on November 18, 2005, after approvals from 36 state commissions, the DOJ, the FCC, and foreign regulatory bodies across more than a dozen countries. AT&T reemerged not as a relic but as a platform—positioned to invest in fiber, wireless spectrum, and eventually, content distribution. Whether the merger "worked" depends on your metrics. From a regulatory strategy perspective, it was executed with remarkable precision.

Today, when I read about mega-mergers, I rarely think in terms of stock price or EBITDA multiples. I think in terms of narrative risk, message control, and stakeholder psychology. I think about how a 28-year-old professional found himself fielding questions from reporters, working with the former speaker of the California Assembly, strategizing with lobbyists, and drafting materials for some of the most powerful executives in American business.

And I remember the lesson that matters most: In moments of complexity, clarity is a form of leadership.

Sidebar: Lessons from the War Room

- Narrative is Power. Don’t let facts speak for themselves; facts require framing.

- Local Matters. Federal approval may drive headlines, but state regulators shape outcomes.

- Opposition is Predictable. Most critics recycle talking points; rebuttals should evolve but remain anchored.

- Youth Is Not a Liability. In high-stakes environments, curiosity and stamina often trump tenure.

- Coordination Is Strategy. A message unshared is a message unmade.

This is the first time I’ve reflected publicly on my role in the merger. Perhaps it’s because I now appreciate not just the historical significance, but the personal one. For a brief moment in time, I stood at the intersection of policy, commerce, and narrative. And I learned that even in the shadows of giants, one can find space to stand tall.

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Member discussion